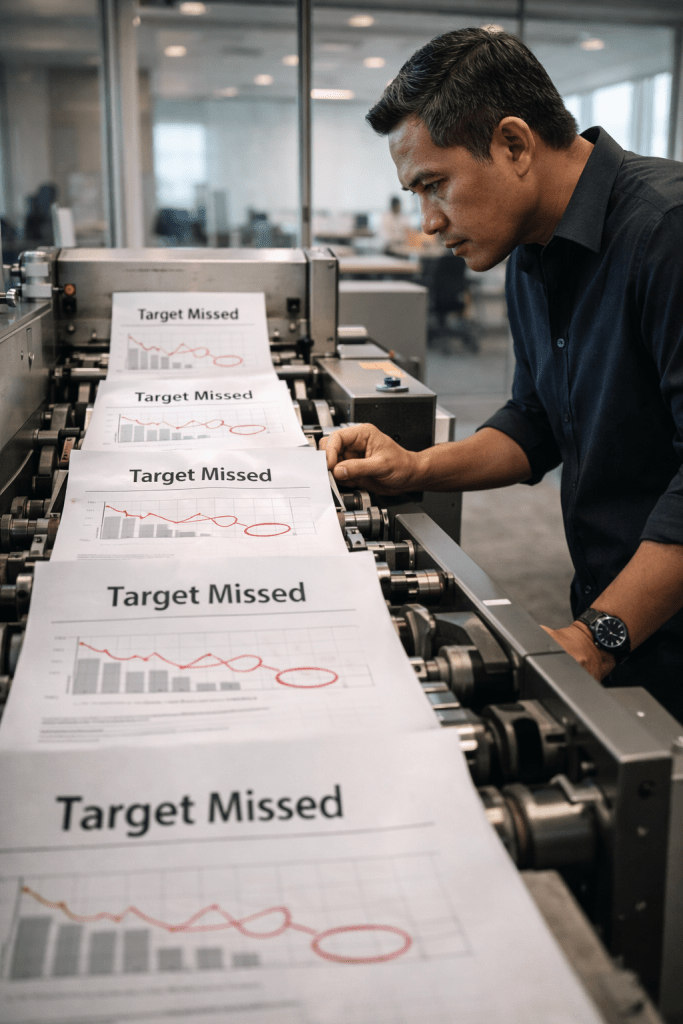

When targets are missed, the instinct is immediate.

Push harder.

Set clearer KPIs.

Increase accountability.

“Raise the bar.”

It feels logical. If performance is low, pressure must be low.

But here’s the uncomfortable reality most companies avoid:

Performance usually breaks after ownership breaks.

And ownership breaks quietly.

It doesn’t show up as rebellion. It doesn’t look like laziness. It looks like meetings. Alignment. Escalation. Professional caution.

That’s how you know it’s structural.

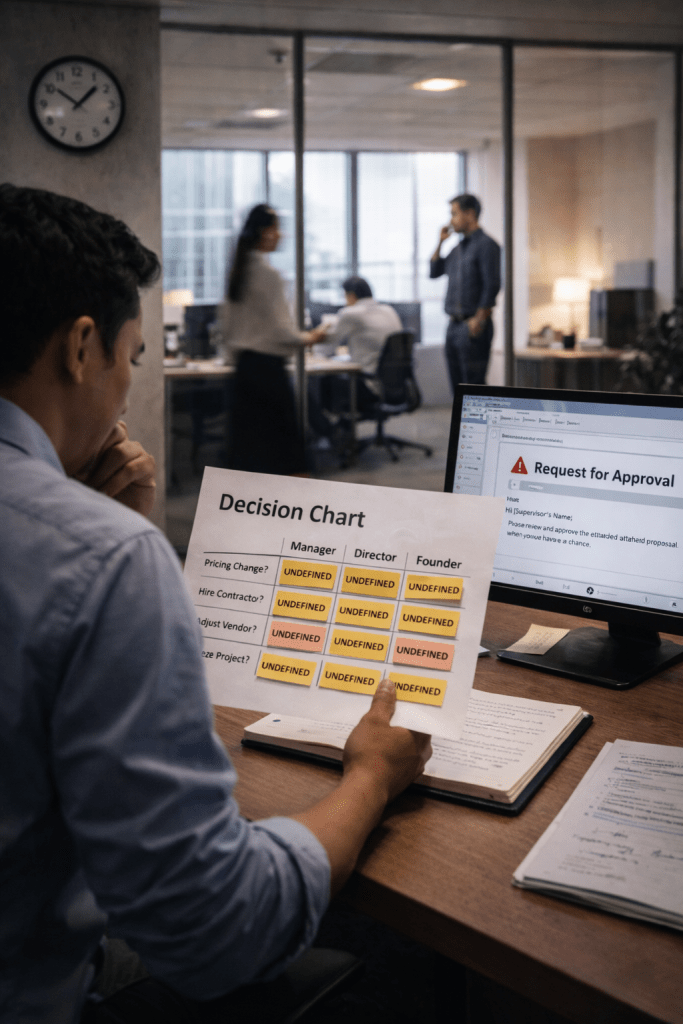

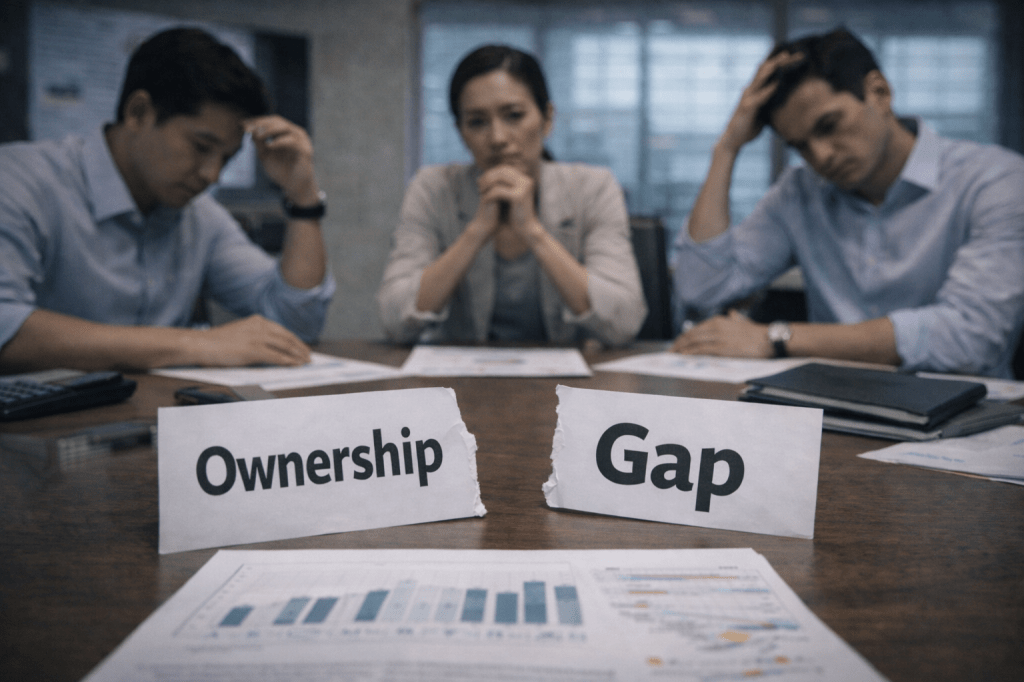

Let’s say a revenue target is behind. Sales says marketing didn’t generate enough leads. Marketing says sales didn’t convert fast enough. Operations says delivery constraints slowed deals. Everyone has a valid explanation.

But very few people can answer one simple question clearly:

Who owns the outcome end-to-end?

Not the activity.

Not the metric.

The outcome.

When ownership is fragmented, performance gets diffused. Each department optimizes its own slice. No one owns the full result. So when numbers slip, the system produces explanations instead of corrections.

This is the ownership gap.

Managers sit in the middle of it.

They are responsible for performance—but not always empowered to make the decisions that affect it. Authority is partial. Boundaries are vague. So instead of deciding boldly, they coordinate carefully.

They escalate trade-offs.

They request alignment.

They wait for final approval.

Escalation feels responsible. But every unnecessary escalation signals something deeper: ownership wasn’t clear enough to absorb risk.

And risk has to go somewhere.

So it travels upward.

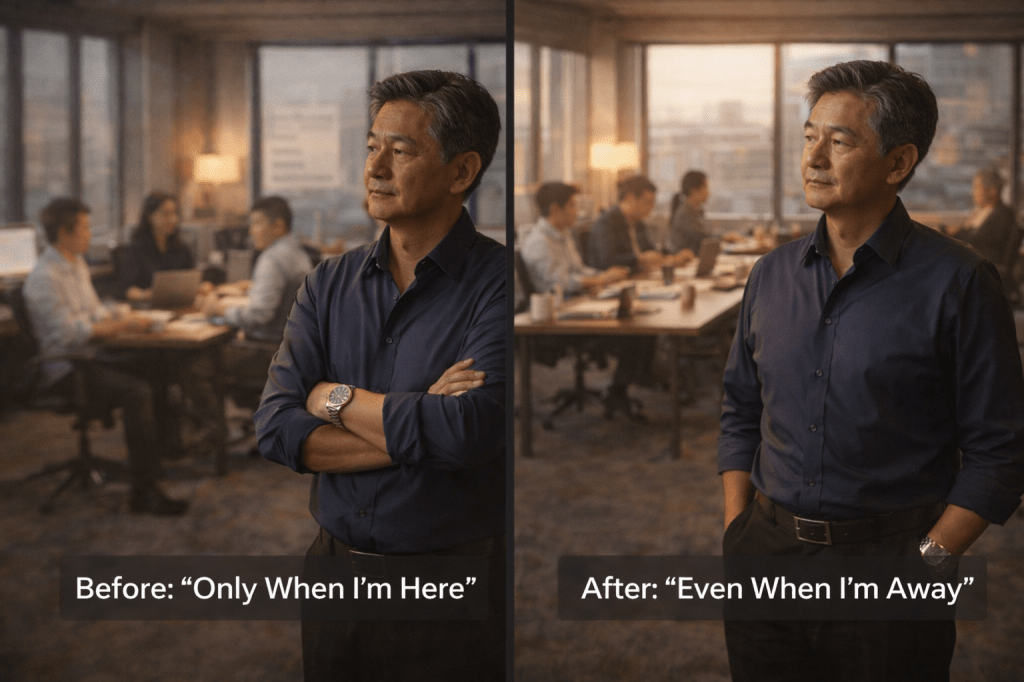

Founder bottlenecks often form here—not because founders demand control, but because unresolved ownership creates vacuum pressure. If no one fully owns the decision, the highest authority becomes the default owner.

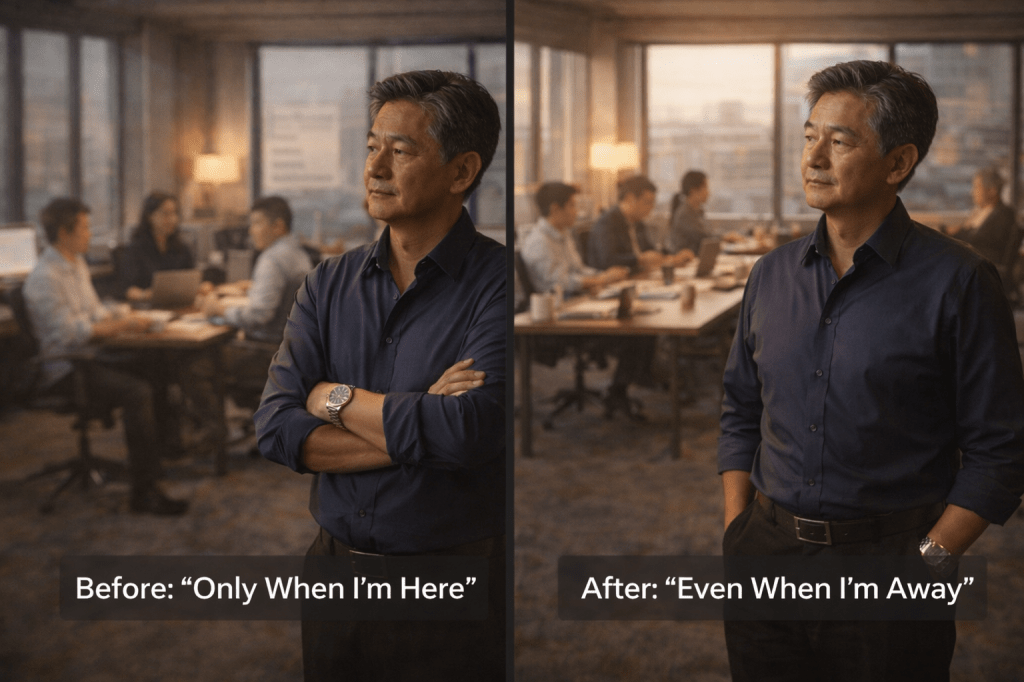

This creates a cycle.

Managers escalate because ownership is unclear.

Founders decide because someone has to.

Managers learn that decisions ultimately live above them.

Next time, they escalate faster.

Meanwhile, performance conversations get louder.

More reviews.

More dashboards.

More check-ins.

But none of that closes the ownership gap.

You cannot performance-manage your way out of structural ambiguity.

If a manager cannot say, “This outcome is mine—and I have the authority to decide what affects it,” then performance will always feel heavier than it should.

Targets won’t be missed because people don’t care.

They’ll be missed because ownership was split into pieces too small to carry the weight.

The hard truth is this:

Most performance problems are delayed ownership problems.

By the time numbers are reviewed, the real issue has already happened—weeks earlier—when a decision floated instead of landing.

You don’t need more pressure.

You need clearer lines.

Clear owners.

Clear decision rights.

Clear consequences.

Because when ownership is whole, performance sharpens.

When ownership is fragmented, performance fractures.

And no amount of motivation fixes a gap in structure.